Being a good father these days is a practice that can bring me to my knees and give me wings sometimes in the same day.

Today’s Wonder Dispatch is a series of brief reflections on a kind of perception we can practice toward our children, our teams, and ourselves.

I do not typically write about being a father - even though it is among my most important jobs right now. It occupies a lot of my attention. So, why not?

In this Wonder Dispatch:

Jeffrey’s Main Musing: on feathers, leaders, and perceptive genius

Ask Me Anything spots

These days, the 11-year-old keeps stepping forward and throwing her hat in the ring, so to speak. She comes home announcing what’s next.

A woodworking workshop? She’s in.

Run for PTSA rep after three weeks at a new school? Why not?

Play the oboe in a nationally ranked music program? Sure (blow-and-bear-it).

Learn field hockey from scratch? Yes.

She’s several inches shorter than most of her peers. Last year, a tall friend used to hug her and sing a made-up song called “The Little One.” She took it in stride. Still, not long ago she asked me,

“Papa, how much taller do you think I’ll get?”

“In your life?”

“Yes.”

“Maybe a foot or so.”

She looked off. “That’s so sad.”

We talked about why she wanted to be taller. I tried, best I could, to talk with her about expectations, what people assume because you're a girl or small or quiet, and how those expectations can be defied.

“You’re focused,” I told her. “You’re one of the most observant people I know. That alone will carry you far.”

It’s true. When she was a toddler, my friends would try to make her giggle with baby talk. She’d hold their gaze instead with no smile until she chose to give one.

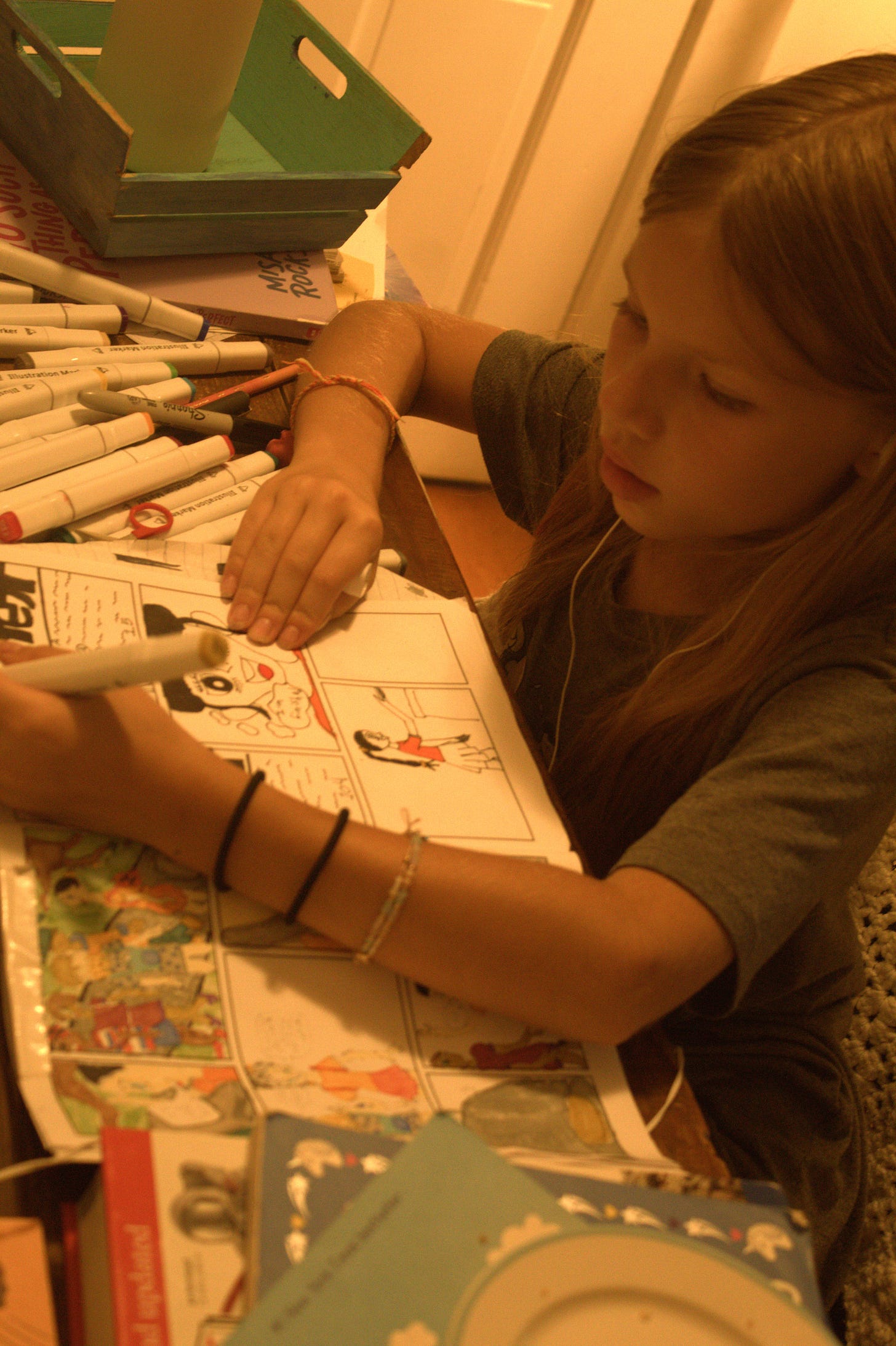

Since she could speak, if someone in the family misplaces something, she’s been the one to find my wallet, her mother’s glasses, the moved vase. That same precision led her to teach herself how to make a graphic novella, frame by frame, angle by angle.

The 11-year-old recently joined a countywide field hockey clinic with kids from eight schools, all levels. At registration, her coach saw her and lit up.

“I’m so glad you’re here! You have so much grit!”

The coach looked to me and said, “She is so quiet, but so gritty! So gritty! She’s great on defense!”

My daughter stood calm, half-smiling. I felt something tighten in my throat.

I could tell she had defied expectations. But more than that, she had been seen. The coach recognized a force in her she might not yet see in herself.

That coach perceived her genius.

Quick note: I’m really happy so many people enjoyed the first Shot of Wonder last week. If you’ve not already done so, consider getting access to the new Shots of Wonder videos, deep dive practical articles on wonder & work, and chacnes to connect more with our Wonder HUB community.

Genius is a force of character we’re born with.

But we enter life in wonder, open and not-knowing, so we forget.

We remember in flashes such as when we’re absorbed in something that calls on our strengths, or when someone sees a quality in us we hadn’t seen ourselves.

In that moment of being seen, the veil of forgetting lifts.

I first came across this way of thinking about genius years ago while studying Greek philosophy and Jungian thinker James Hillman’s writings at the same time. In a book on parenting, written during a time when blame was often laid at the feet of parents, Hillman argued that a parent’s job isn’t to make a child happy. It’s to work with the world so the child’s genius (contradictory, wild, or quiet) can have a life. Fatherhood wasn’t even a remote consideration. But I was teaching, and I took Hillman’s idea seriously. Every student carried a distinct genius. My task was to notice.

But there’s a catch, he wrote. To do that, a parent must first bear witness to their own genius.

And then this line, which struck a nerve deep enough that I printed and taped it beside my desk:

“For the father who has abandoned the small voice of his unique genius… cannot bear reminders of what he has neglected. He cannot tolerate the idealism that arises so naturally and spontaneously in the child, the romantic enthusiasms, the sense of fairness, the clear-eyed beauty, the attachment to little things, and the interest in big questions.”

I wasn’t a father then, but I understood what was at stake.

Later, Hillman described something he called perceptive genius, which is the gift to see the genius in others. Hillman tells how William James recognized a young, awkward, gangly Gertrude Stein’s brilliance when others dismissed her.

I think of the coach who saw leadership in a 10-year-old Mike Erwin, as he shared on the Tracking Wonder Podcast, who has gone on to become CEO of the Character & Leadership Center. I think of the field hockey coach who looked at my daughter (small, quiet, fierce) and called her gritty.

That kind of seeing has been my fatherly aim since the beginning. To recognize the genius in each daughter, to support it when I can and to trust it when I can’t.

Admiration—the mirror facet of wonder—often begins here.

Admiration I define as a surprising love for someone’s excellence in character or craft. That’s what I heard in the coach’s voice.

describes attention as “an instrument of love” (h/t, Jeannie Forest). Attention is that not only how much but especially how well or with what quality we pay attention.Years ago, I worked with a company president who lit up when he talked about finding hidden strengths in his people and helping them grow. I could feel his love. We shaped a new role for him, one that also honored that part of his perceptive genius.

You don’t need a title to practice it. On a nonprofit board, one member I worked with had a gift for noticing very specific contributions in others. Her presence shifted how we saw one another with mutual respect for our differences in temperament and talent.

I’ve trained teams from creative tech teams to button-down finance teams to learn how to do this. At first, they’re skeptical. Then the mood changes. They feel mutual respect, trust, and regard that elevates how they connect, collaborate, and care for each other.

That’s perceptive genius at work.

Being a father is not easy. It is a practice.

Profoundly rewarding. But still a practice. Whether I want to get better as a speaker, an entrepreneur, a writer, a husband, a friend, or a father, I need to practice. It requires attention, repetition, and humility.

When my older daughter was just a few months old, I took her out for a walk in a front-facing chest pack. I stopped at one point, looked into those sky-wide blue eyes, and made a quiet vow.

Two, actually.

First, I pledged to let her teach me again the art of not-knowing. Second, I vowed to live a life of such creativity and wonder that when her time came to grow up, she wouldn’t fear adulthood but would welcome it. I’ve fallen short on both vows more times than I’d like to admit.

Now, as I watch her wrestle with the pressures of achievement, college, and questions about her future, I find myself returning again to Hillman’s central truth:

It’s not my job to make her happy. It’s not even my job to ensure her genius flourishes.

It’s my task to tend to my own genius, first and continually, and to keep doing the work in this unpredictable, aching, radiant world so that hers might have a place to grow.

This, I’m learning, is part of the quiet heartbreak and grace of parenting:

That it’s through recognizing and accepting the contradictions of my own genius that I’ll be able to let go, when the time comes, and trust these two astonishing human beings to make their way into the world.

Perceptive Genius

Your genius is not just what you do well. It’s a particular way you meet the world in terms of how you listen, how you make, how you care, how you show up.

To notice it is a practice.

To notice it in others is a gift.

Try this:

Remember a time when you were younger and felt most alive and free.

Recognize what qualities came through in you.

Activate those qualities again—today.

Reclaim them when life tries to make you forget.

Those are the 4 Pillars of Young Genius at Work.

Your Turn to Wonder

»> When was the last time you truly saw someone’s hidden strength or spark and let them know?

»> Whose quiet genius shaped your own?

»> What part of your own character (distinctive, maybe even contradictory) wants to be recognized, practiced, and lived more fully this season?

You’re welcome to reply and share with me or post in this week’s Wonder HUB thread.

Pause. Gaze. Admire.

Let that small act of wonder be the start of remembering.

Maybe at times this is all any of us can offer one another: To practice the art of seeing, to risk being seen, and to remember what’s been with us from the start.

Ask Me Anything

If you want to ask me a question about this or anything else that might merit a Canoe Talk response, fire away here. Or drop a question in the Wonder HUB thread.

I appreciate your being here and showing up for the work that matters most in this one life.

I’ll see you next Sunday for the next Wonder Dispatch if not sooner.

Thanks for running with me,

Jeffrey

Reintroduction to new trackers: I’m author of Tracking Wonder (Sounds True), a Next Big Idea Club finalist. Fast Company, MindBody Green, Psychology Today, and other leading outlets - I’m grateful to say - have featured my insights.

For over 25 years, I’ve equipped entrepreneurs, creatives, and teams to think more expansively and bring more meaning into their work so they can advance what matters most. Without burnout. Learn more about this work and The Wonder HUB here.

I substituted the word "mother" for "father." Going deeper into more self-awareness hoping to understand how to be a positive voice at this time of my life. Thank you Jeffrey.